Gwen van den Eijnde is a French and Dutch artist and costume designer based in the United States. For the past decade, he has been teaching apparel design at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, where he currently serves as the head of the program.

While pursuing personal artistic research at the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg, he began to create costumes as sculptural pieces. His approach emphasizes how wearing costumes influences one’s presence in space. He has crafted visual worlds and atmospheres through performances, installations, and photographs, allowing the costumes to unfold a complete scenography. His performances have been conducted in international contexts—including artist residencies, museums, schools, festivals, theaters, and workshops—often in collaboration with artists from diverse disciplines.

In 2011, he led a workshop in the fashion department of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, sharing his interest in Polish traditional dress with students. He later taught textile design at the Haute École des Arts du Rhin in Mulhouse (France) and has conducted creative research for fashion houses such as Hermès and Tiffany & Co.

BEMF Opera Director Gilbert Blin invited Gwen van den Eijnde to design costumes for two French chamber operas produced by the Boston Early Music Festival in 2022: L’idylle sur la Paix by Jean-Baptiste Lully and La Fête de Rueil by Marc-Antoine Charpentier. In their latest collaboration on Telemann’s Don Quichotte, they deepen their partnership through ongoing dialogue and practical sessions. This interview outlines the costume design process for the Telemann’s Don Quichotte auf der Hochzeit des Comacho, emphasizing a sculptural and embodied approach.

Fig 1. Caption

Q: How do you conceive costumes for a production of an opera?

A: My creative process is quite personal and differs from traditional costume design. I work as a polychrome sculptor, focusing on the sculptural qualities of fabric and materials on the performers’ bodies through multiple fitting sessions, rather than relying on sketches. I bring this same embodied approach to my classroom at RISD.

Q: How does this process relate to the dramaturgy of the piece and the production style of the Boston Early Music Festival?

A: I’m excited to collaborate again with opera director Gilbert Blin on Telemann’s Don Quichotte auf der Hochzeit des Comacho. Gilbert has a unique insight into how costumes can help define character identity. Since this chamber opera lacks a specific set design, the costumes must convey a distinct sense of time and place.

Q: Can you describe the concept of a research-based fantasy that creates an imaginary reality yet remains a concrete and living image on the actors’ bodies?

A: Absolutely. Each costume is designed to enhance the identity of individual characters, while some costumes visually represent groups, aiding the audience’s understanding of the drama. The opera centers around the wedding scene of Comacho and Quiteria, viewed by Don Quichotte and Sancho Pansa as a “tableau vivant,” making the visual aspect particularly significant.

Q: How did you plan your work?

A: My costume conception is grounded in extensive research into 18th-century Spanish attire. While not a historical reconstruction, the designs reflect traditional Spanish styles and incorporate elements reminiscent of Provençal costumes. The costumes are informed by historical references yet remain inventive, incorporating various influences from art, fashion, and textiles for the viewer to engage with.

Q: How do you address sustainability in your work?

A: The costumes must be visually captivating and relevant to contemporary audiences. This project allowed me to create an original representation of 18th-century Spanish fashion using rich documentation. I combined existing pieces from the BEMF costume reserve with new garments, sometimes utilizing recycled materials.

Q: How is the Spanish setting reflected in the costumes?

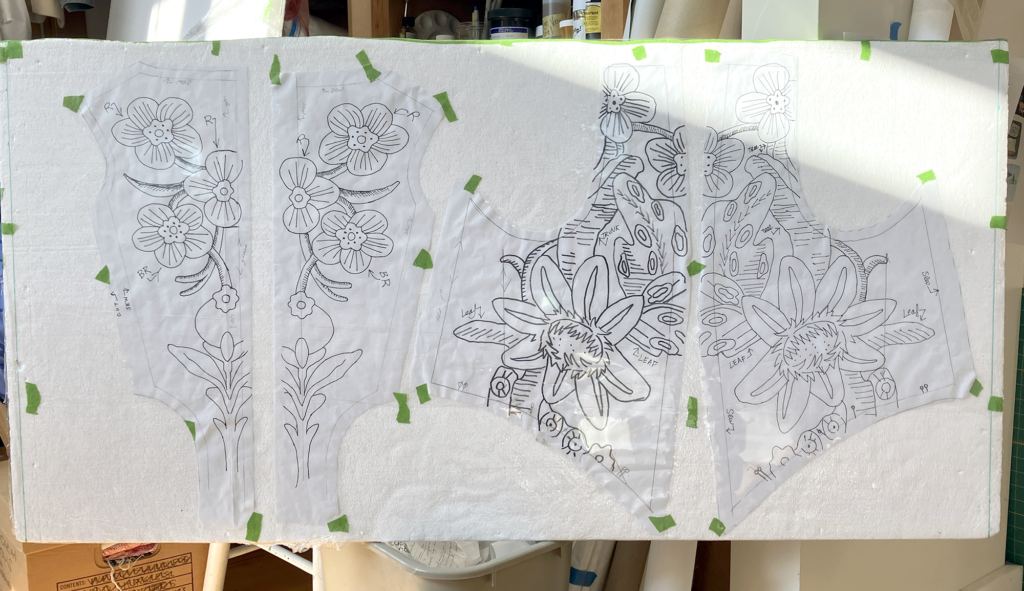

A: The selection of fabrics and colors evokes a festive atmosphere reminiscent of the warm, sunlit Mediterranean. Female characters at the wedding wear vibrant skirts with printed borders and decorative aprons. Textile artist June House crafted hand-painted motifs inspired by antique fabrics, including floral chintz and dominoté paper designs (an early modern form of decorative paper used mostly on book covers).

Q: How did you integrate these motifs into your costumes?

A: The bridal costumes feature visual correspondences: Comacho’s long waistcoat is painted with a tree of life motif similar to Palampore fabrics, while Quiteria’s casaquin jacket showcases pomegranate flowers arranged to complement the garment’s cut. Quiteria’s look is completed with an ivory Spanish comb supporting a mantilla, and her luxurious skirt was tailored from a thrift store curtain.

Comacho’s waistcoat is secured by 18 hand-made thread buttons, in a shade of pink to match the fabric. Examples can be found in portraits of merchants, members of the well-to-do upper middle class, and on surviving garments of the 18th century. These buttons would have appealed to someone who could afford quality.

Fig 2–4. Caption

Q: What about the “papiers dominotés”?

A: The shepherds are dressed in vests with motifs inspired by dominotés papers, creating a unique visual identity. Domino papers were used to cover books, boxes, chests, and sometimes even walls of small rooms, acting as a decorative alternative to fabric or wallpaper. Since these bespoke fabrics are rare, the vest designs were hand-painted by June House, mimicking the irregularity of block printing on paper.

Fig 5–6. Caption

Q: How did you handle the danced pantomime presented by Comacho to entertain his bride?

A: The shepherds transform into allegorical characters, their identities depicted on long parchment ribbons wrapped around their bodies, echoing Cervantes’ imagery. The masked and veiled silhouettes add an enigmatic quality to the scene, reminiscent of the works of Jacques Bellange, the costume designer contemporary of Cervantes.

Q: Costuming Don Quichotte may seem straightforward, but how did you avoid stereotypes?

A: The costumes for Don Quichotte and Sancho Pansa provide an opportunity to innovate beyond the stereotypes associated with these iconic characters, frequently represented in art from Coypel to Salvador Dalí. The Sancho costume incorporates an existing piece, while Don Quichotte’s silhouette is created using recognizable elements like armor, a barber’s plate hat, and a shield, all infused with original touches and surprising details.